“It wasn’t that the city was lawless. It had plenty of laws. It just didn’t offer many opportunities not to break them.” —Night Watch (2002)

In the Discworld series, Ankh-Morpork is the Ur-city, of which all other cities throughout time and space are mere echoes. But politics is, quite literally, the life of the polis, of the city, as Pratchett himself was keenly aware:

“‘Polis’ used to mean ‘city’, said Carrot. That’s what policeman means: ‘a man for the city’. Not many people knew that.” —Men at Arms (1993)

And again, in the finale of the same book: “Have you ever wondered where the word ‘politician’ comes from?” said the Patrician.” It is therefore little wonder that politics, and political philosophy, is a core subject of most, if not all, of Pratchett’s works at some level or another—and this is especially true of the Discworld novels

After all, the strength of the Tao of Sir Terry rests firmly on a bedrock of satire, and what better target for satire than politics? But, as ever with Pratchett, that satire is never vain or gratuitous, and always contains a philosophical bent that leads us to question the status quo; it’s satire that takes up surprising political stances, ranging from cynicism and suspicion of power to a brave, humanist outlook that fuels a deep-rooted hope for a responsible political future.

If there was anything that depressed him more than his own cynicism, it was that quite often it still wasn’t as cynical as real life.

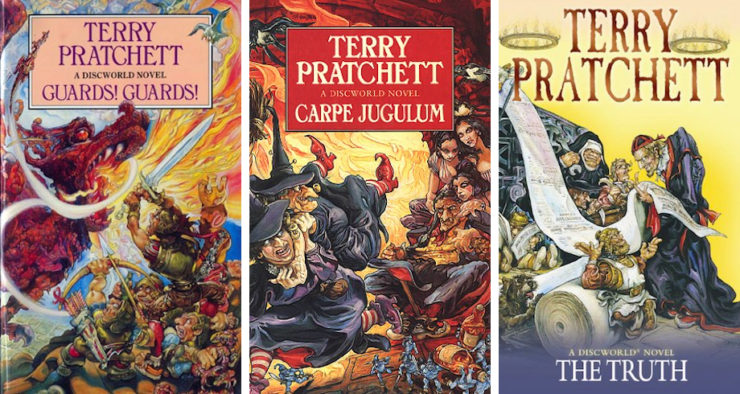

—Guards! Guards! (1989)

The first, and easiest, level of political philosophy in Sir Terry’s works is, of course, satire of power and those who wield it, with a healthy dose of defiance and derision of established authority to boot…

Technically, the city of Ankh-Morpork is a Tyranny, which is not always the same thing as a monarchy, and in fact even the post of Tyrant has been somewhat redefined by the incumbent, Lord Vetinari, as the only form of democracy that works. Everyone is entitled to vote, unless disqualified by reason of age or not being Lord Vetinari.

—Unseen Academicals (2009)

This is clearly not cynicism in the philosophical sense—quite the contrary, since one of the central tenets of the Cynic is to live in accordance with nature and reject any quest for power. But it certainly employs cynicism in the modern, common usage of the term, to great comedic effect, from the manipulation of useless committees to Disc-spanning geopolitical issues resolved by the careful placing of people, like pawns, in the right place at the right time.

Pratchett takes this critical view of the modern nation-state into even greater detail, describing the political process as institutionalised trickery, especially when it comes to taxation. For example:

“‘Listen, Peaches, trickery is what humans are all about,’ said the voice of Maurice. ‘They’re so keen on tricking one another all the time that they elect governments to do it for them.’” —The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents (2001)

“Taxation, gentlemen, is very much like dairy farming. The task is to extract the maximum amount of milk with the minimum amount of moo.” —Jingo (1997)

“On the fifth day the Governor of the town called all the tribal chieftains to an audience in the market square, to hear their grievances. He didn’t always do anything about them, but at least they got heard, and he nodded a lot, and everyone felt better about it at least until they got home. This is politics.” —The Carpet People (1971)

This vision of politics as a distasteful but necessary expedient is on par with the pragmatist and consequentialist political philosophies of the European Renaissance, as exemplified by the work of philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes. The latter’s concept of the social contract is echoed in Pratchett’s work as well, and both would agree that, as a system based in the inherent selfishness of the individual, the political system produced by the social contract will only ever be as just, as noble, and as ethical as its citizens want it to be. As Lord Vetinari explains to Vimes in Guards! Guards!—

Down there—he said—are people who will follow any dragon, worship any god, ignore any inequity. All out of a kind of humdrum, everyday badness. Not the really high, creative loathsomeness of the great sinners, but a sort of mass-produced darkness of the soul. Sin, you might say, without a trace of originality. They accept evil not because they say yes, but because they don’t say no.

“Verence was technically an absolute ruler and would continue to be so provided he didn’t make the mistake of repeatedly asking Lancrestrians to do anything they didn’t want to do.”

—Carpe Jugulum (1998)

If the social contract produces political systems as petty and vile as the citizens themselves, then the opposite is also true—and this is the saving grace of the political systems Sir Terry develops throughout his work: a deep-rooted belief in the fundamental goodness of humankind and in our ability to strive towards greater social justice, however difficult or ridiculous the path towards it may be.

As Pratchett tells us in The Night Watch (2002):

“Vimes found it better to look at Authority for orders and then filter those orders through a fine mesh of common sense, adding a generous scoop of creative misunderstanding and maybe even incipient deafness if circumstances demanded, because Authority rarely descended to street level.”

Or consider Polly Perks’ reasoning in Monstrous Regiment (2003):

“And if you couldn’t trust the government, who could you trust? Very nearly everyone, come to think of it….”

This basic faith in the individual (and the individual’s ability to contend with authority) reveals the true essence of Sir Terry’s political philosophy: humanism, a belief in individual freedom and responsibility, human values and compassion, and the need for tolerance and cooperation, especially in the face of authoritarian systems. In this, Pratchett is part of an unbroken chain of thinkers and writers going back to ancient Indian, Chinese, and Greek philosophers, through Medival Muslim thinkers, and passed along through the likes of Petrarch, Rabelais, Montaigne, and Bertrand Russell.

Moreover, Pratchett’s fundamental faith in humankind is such that even his Tyrants contract a healthy dose of goodness, as if ethics were a contagious disease:

“Any sensible ruler would have killed off Leonard, and Lord Vetinari was extremely sensible and often wondered why he had not done so.” —Jingo (1997)

“I’m sure we can all pull together, sir.”

“Oh, I do hope not. Pulling together is the aim of despotism and tyranny. Free men pull in all kinds of directions.”

—The Truth, (2000)

Pratchett’s belief in the ability of humankind, from the man in the field to the man in the Palace, to be good and make ethical choices forms the basis for the strongest, bravest, and most hopeful political philosophy developed throughout his works: meliorism, perhaps best formulated by the Marquis de Condorcet. Meliorism holds that progress is both real and possible, and that people can, through their actions and their choices, improve the world step by step, as opposed to passively accepting the state of nature and the status quo.

Lord Vetinari himself seems to say as much in Unseen Academicals (2009): “And that’s when I first learned about evil. It is built into the very nature of the universe. Every world spins in pain. If there is any kind of supreme being, I told myself, it is up to all of us to become his moral superior.”

It is this stance that reconciles the two seeming opposite poles of Pratchett’s political philosophy: his cynical distrust of authority and his fundamental humanism. In Sir Terry’s worlds, even absolute Tyranny can be moral, so long as it remains “the only form of democracy that works,” with emphasis on the “works,” even if that places it at complete odds with and in deep suspicion of itself. Consider this exchange between Lord Vetinari and Vimes:

“Commander, I always used to consider that you had a definite anti-authoritarian streak in you.”

“Sir?”

“It seems that you have managed to retain this even though you are authority.”

“Sir?”

“That’s practically zen.”

—Feet of Clay (1996)

Or course, nobody said that doing good work and improving the world was ever going to be popular, or even respectable, either for a political system or for any individual government:

“Verence II was the most amiable monarch in the history of Lancre. His subjects regarded him with the sort of good-natured contempt that is the fate of all those who work quietly and conscientiously for the public good.” —Lords and Ladies (1992)

But as Pratchett himself said, you can’t make people happy by law.

The works of Sir Terry Pratchett are a rich smorgasbord of political systems and philosophies, denouncing the faults of our own societies as seen through the dual lenses of satire and good-natured ribbing. While those who deem themselves to be in power are often the best butts of the great Pratchettian joke, Sir Terry’s fundamentally humanist message is as cutting as it is serious, and remarkably prescient—and it is certainly needed today more than at any other time since the Turtle started moving.

J.R.H. Lawless is a multiple award-winning Canadian SF author who blends comedy with political themes — drawing heavily, in both cases, on his experience as a lawyer and as Secretary General of a Parliamentary group at the French National Assembly. A member of SFWA and Codex Writers, his short fiction has been published in many professional venues, including foreign sales. He is also a craft article contributor to the SFWA blog, the SFWA Bulletin, and Tor.com. His first novel, Always Greener, is coming out in Fall 2019 from Uproar Books. He is represented by Marisa Corvisiero at the Corvisiero Literary Agency, and would love to hear from you on Twitter, over at @SpaceLawyerSF!

In one of the citations Unseen Academicals is incorrectly dated as 2015 rather than 2009.

Another relevant Vetinari quote from Unseen Academicals:

“People do not understand the limits of tyranny. They think that because I can do what I like, I can do what I like. A moment’s thought reveals that this cannot be so.”

He’s a ruler who knows — and cares — that even though he’s the most powerful person around, his actions can have consequences, for himself as well as others, that he doesn’t want.

@1: Fixed!

“Verence was technically an absolute ruler and would continue to be so provided he didn’t make the mistake of repeatedly asking Lancrestrians to do anything they didn’t want to do.”

This sort of thing also betrays that Pratchett was a student of the British constitution, whose stability depends on the fact that the Queen has, on paper, a great deal of power* which everyone including the Queen thinks it best that she never uses.

*No bill can become law if she witholds the Royal Assent, no prime minister, cabinet minister, ambassador, military officer or even bishop can take office unless the Queen decides, no prosecution can proceed without the consent of the Crown. It’s even arguable that only the Queen has the power to order a nuclear strike. However, it is vital that she never make the mistake of doing any of this stuff.

And this is very good advice too, for anyone in a chain of command:

“Vimes found it better to look at Authority for orders and then filter those orders through a fine mesh of common sense, adding a generous scoop of creative misunderstanding and maybe even incipient deafness if circumstances demanded, because Authority rarely descended to street level.”

It’s fundamental to any hierarchical organisation that information flows up and orders flow down. The lance-constable on the street corner hears a rumour about an upcoming blagging at Bearhugger’s Distillery, he passes it up to his corporal, who tells his sergeant, and the sergeant mentions it to the captain, who decides: right, sergeant, that’s in your patch, put an extra man on patrol tonight, and the sergeant tells the corporal, who tells a constable to shift his route. Right?

But the problem is that not all information makes it all the way up. It can’t. There has to be a filtering process at each level because there’s only so much time to pass on information, so the corporal has to decide what’s worth passing on and what isn’t, and so forth. So the man on the ground is always going to have more information about his immediate situation than the man at the top, and so it’s his job to do what he thinks the captain would want him to do, which may not be exactly what the captain has actually told him to do.

@Ajay.

*See also the 1975 constitutional crisis in Australia. It more or less boiled down to “You can stay our Queen if you make sure this never happens again.”

The scary thing isn’t that the Queen can order a nuclear attack – as Sovereign she is above the laws – but that Charlie also can.

Because the Crown includes the Duchy of Cornwall (and Lancaster), he gets his exemption that way. The key is that the Crown is a state body, but Charlie *is* the Duchy of Cornwall. Apparently he gets a lot of exemptions because the UK requires the Queen’s Consent for legislation to become law, and also the Prince’s Consent for anything touching on the rights of the Duchy. He threatens a veto, they quietly include the exemption, law passes. I suspect ER also technically gets the same exemptions as the Duke of Lancaster, though being Queen would supersede that.

But one of the key laws he is exempt to is the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998, which makes it illegal for any British person to set off a nuclear explosion unless done under instructions in the course of an armed conflict.

Amusingly this means that Parliament has to make a specific exemption if they want to nuke Australia again to see if the crackers still work or else their sailors are breaking the law.

The scary thing isn’t that the Queen can order a nuclear attack – as Sovereign she is above the laws – but that Charlie also can.

I think that just means that he, like the PM, can veto an attack; he can’t order one because he isn’t in the military chain of command (unless HM puts him there).

Fun fact: the famous “nuclear codes” that appear in so many techno thrillers, that make it impossible for a rogue US missile commander to launch a strike on his own? The UK doesn’t have any. We take the view that it requires the consent of the sub commander and his WSO to launch, and that’s enough. They are officers of the Royal Navy, and, as the Navy put it when the question was raised, “It would be invidious to suggest… that senior Service officers may, in difficult circumstances, act in defiance of their clear orders.”

@Ajay and Mayhem –

This is pretty much the premise of the play Charles III by Mike Bartlett: Charles becomes king and triggers a constitutional crisis by refusing to give the royal assent to a particular bill. There’s a pretty decent TV adaptation of it (by Bartlett) if you can’t see it on stage.

” If there is any kind of supreme being, I told myself, it is up to all of us to become his moral superior.”

my god, I miss that man and his unique combination of rage and joy.

The Tao of Pratchett, as stated by Harry Dresden,

“Give a man a fire and he’s warm for a day, but set fire to him and he’s warm for the rest of his life.”

I enjoyed Sir Terry’s contribution to the world, and still feel that it is a darker place without him. We should all endeavor to live in the place where the falling angel meets the rising ape.

@@.-@, Luckily the English monarchs since George V have been dedicated constitutionalists, Edward VIII was the exception. Thank God for Wallis Simpson.

Luckily the English monarchs since George V have been dedicated constitutionalists, Edward VIII was the exception.

All two of them.

Hopefully the trend will continue.

I recently did a post of my own on Pratchett’s politics. https://izgad.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-secret-of-ankh-morpork-non-comic.html

Like you, I was struck by how those in power are not really in control of the situation. You see Pratchett as having a cynic’s faith in human goodness. I read Pratchett through a Burke/Hayek lens that focuses on the embedded institutions at play in Ankh-Morpork that bring about liberal results without anyone actually planning that.

Another UK example of having absolute power but not using it because of the consequences is Charles II. He was well aware that his dad was executed and walked a very fine tightrope with Parliament to retain power (but sort of blew it with naming his brother James II as his heir. James did try to weld power, which is why he was disposed). To put in perspective how keen the Brits were not to have a catholic in the line of successor after this fiasco, when Queen Anne died they dropped down to the 50th on the list to find George I.

“Pulling together is the aim of despotism and tyranny. Free men pull in all kinds of directions.’

Good to remember.

This is a wonderful examination of Pratchett’s thoughts on politics. My own reviews of Discworld at https://narrativiumreviews.com haven’t tackled this topic yet, but I will likely check back here when that time comes.